- German

- English

Fog hangs heavily over the Danube as the first factory sirens pierce the morning air. Horse-drawn carts rumble through the streets while black clouds rise from the chimneys. Inside the factory halls, it is often quiet – not because of the work, but because the power has gone out once again. A single switch pull in the power plant, a large consumer starting up its machines, and suddenly the lights flicker, the engines sputter, and production has come to a standstill.

Electricity is the great promise of modernity. It is already a reality in Berlin and other major cities. But in the Upper Palatinate, as in many rural regions, it is still a capricious guest. Island grids supply individual towns, connected by fragile lines that falter with every change in load. When the paper mill in Schwandorf starts up its rollers, you can feel it all the way to Regensburg: lamps flicker, machines stall, and sometimes the grid collapses completely. People curse, engineers despair.

“We need power, reliable power!” rants a factory director at a meeting of Oberpfalzwerke. “Otherwise, we might as well go back to steam engines!” But technology has reached its limits. Transformers cannot be switched under load without interrupting the flow of electricity. Every attempt ends in arcing, flying sparks, and burnt contacts.

It is a time of transition: cities are growing, industry demands more energy, and electricity is set to be the backbone of this new world. But without a solution to voltage fluctuations, the dream of a stable grid – in Bavaria and everywhere else – remains a dangerous adventure.

Within the energy industry, the problem has been hotly debated for years. Three men stand around a large table covered with maps and circuit diagrams. “The grids are too weak for the load changes,” says engineer Krause, tapping a map with his pencil. “Every switching operation brings us to the brink of collapse.”

His colleague nods. “We need transformers that can be switched under load – without causing a voltage collapse.” “That's impossible,” interjects the third. “Switching causes arcing, which destroys everything. We risk short circuits and failures.”

His colleague, Dr. Bernhard Jansen, a young doctor of energy networks from the Siegerland region, adds: “The problem is the arcing. As soon as we interrupt the load current, it jumps across – like lightning. The contacts burn up, and in the worst case, the entire switchgear blows up in our faces.”

“And the alternative?” asks the third man, an engineer named Hartmann, skeptically. “We can't just reinforce the grids. New lines, larger cross-sections – that costs millions and takes years.”

Krause leans back, his forehead wrinkled. "That's exactly the point. We need a solution in the transformer itself. Something that cushions the switching process. Right now, it's a hard cut: contact open – contact closed. The energy finds its own path, and that's the electric arc."

Dr. Jansen draws a sketch on the edge of the plan. “If only we could control the flow of electricity. But how? The switch would have to work at lightning speed, otherwise we will lose stability.”

Hartmann shakes his head. “That sounds like theory. In practice, we have milliseconds before the voltage collapses. And every arc is a risk.” Krause looks out the window, where the factory chimneys are smoking in the distance. “Electrification is the key to the future. But if we don't solve this, regions will remain in the dark.”

The study is small, the air smells of paper and machine oil. Technical drawings, formulas, and notes are piled up on the desk. Outside, horse-drawn carriages clatter over the cobblestones; inside, there is concentrated silence.

Dr. Bernhard Jansen sits bent over a circuit diagram. His glasses slide down to the tip of his nose as he studies the engineers' sketches. He mutters repeatedly: “Electric arc... contact burn-off... voltage drop...”

He picks up a pencil and draws two thick lines – the contacts of a load switch. “The problem is the moment of switching,” he thinks. “When the flow of electricity is abruptly interrupted, the energy seeks its own path—and that is the arc. We have to tame the transition.”

He gets up, goes to the window, and looks at the smoking chimneys of the city. “The factories need stable grids. We can't wait until new lines are built. The solution must lie in the switch.”

Suddenly, he stops. His gaze falls on a sketch of a resistor from an old textbook. “What if we don't stop the current, but slow it down?” He sits down again, his hand trembling with excitement.

“A resistor in the switching path... it could dampen the current flow, prevent arcing. Not a hard cut, but a smooth transition.”

He scribbles a new drawing: a switch with several contact stages, with resistors in between. “First through the resistor, then directly. Fast enough so that the voltage doesn't collapse.”

Jansen leans back, his heart beating faster. “That's it. A high speed resistor-type tap-changer. With this, we can switch transformers under load – without failure, without destruction.”

He smiles, almost incredulously. “This will save electrification.”

The heavy doors of the Patent Office creak as Dr. Bernhard Jansen enters. The smell of paper and ink hangs in the air, mingled with the muffled murmurs of officials poring over mountains of files. Jansen carries a folder under his arm – inconspicuous to the world, but for him, it is the gateway to the future. Inside are the drawings, the calculations, the idea that would change everything.

He pauses for a moment, looks at the tall windows through which the light is shining, and takes a deep breath. “This is it,” he thinks. “Today marks the beginning of a new era.”

His fingers clench the folder tighter. Not out of nervousness, but out of the awareness that these sheets are more than technical sketches. They are a promise: uninterrupted power, stable grids, a world that can rely on electricity.

As he signs the application, a thought flashes through his mind. The city he sees every day from his office window, with its alleys, workshops, and factories. How often had he seen the lights flicker and machines stand still because the grid was fluctuating? “If we can do this,” he said to himself, “no factory will ever stand still again. And not just here. Everywhere.”

He imagines what the future will look like: factories producing day and night, cities shining in the glow of electric light, households relying on electricity like water from the tap.

And someday – yes, someday – this invention would connect the world. From Bavaria to America, from Europe to Asia. An invisible network, stable and strong, carried by an idea that began today in this room.

Jansen puts down his fountain pen, looks at the official, and nods. “I hereby apply for a patent for the high-speed resistor-type tap-changer.” His voice is calm, but inside he is buzzing with excitement. He knows that this is no ordinary day. This is the beginning of an electrical revolution.

“I can’t believe nobody’s managed it!” exclaimed Dr. Bernhard Jansen, crumpling up the letter from yet another metalworking shop. The gear is still lying on his desk. A gear with a drilled hole in it. The young engineer from Hanover, who has only been in Regensburg for a few weeks in Regensburg and is the technical director at the Oberpfalzwerke, stares at it angrily. This bloody drill! Why can’t anyone build it?

What use is a patent to him if he can’t find someone to build his tap-changer?

Jansen goes back to his desk and looks through the rest of yesterday’s correspondence. It is a dreary day so he switches on his desk lamp.

His office door opens. Miss Egelhofer enters with his tea, followed by his engineer Landauer. “With all due respect, Director, have we really tried absolutely everything in our power?”

“What do you think I’ve been doing all this time? Reading the newspaper? I just can’t find a locksmithwho can make me this damn gear, let alone the rest of it!” says Jansen, slumping in his seat and shaking his head in exasperation. “It’s getting ridiculous.”

“I might know someone else who could help: Kare Scheubeck from Reinhausen, a friend of mine.”

“Kare?”

“Well, his full name is Oskar. He runs a metalworking shop with his brother and builds all kinds of things. He’s a clever fellow.”

“Very well then, why not. In the worst case he’ll just be the seventh person who can’t do it. I’ll go there myself. . Tell your friend know I’m coming. Tomorrow morning at nine o’clock.”

“Will do, Sir.”

Reinhausen, 5 November 1929,

8:30 a.m.

Oskar Scheubeck rubs his temples. This headache is driving him to distraction. He had barely slept for days. He is wondering which would come first: bankruptcy or a restful night.

“Jansen from Oberpfalzwerke is coming today, isn’t he?”

Richard’s voice interrupts his thoughts. “Yes that’s right; he’ll be here soon.”

“Will you talk to him? I have to go to the bank with father soon to ask for a repayment deferral.”

“Will do.”

“Oskar, listen. This is very serious. Even if the bank accommodates our request, it’s only a matter of time. We need something new. Something that works, preferably for a long time. Maybe Jansen can give us something like that. Be polite and helpful, all right? And remember: it’s Doctor Jansen. Doctor – don’t forget. That’s important to a Prussian.”

Richard throws on his coat and goes out of the workshop into the morning drizzle. Meanwhile, Oskar Scheubeck takes a sip of ground coffee. It’s the only luxury they can afford at the moment.

There is a knock on the door.

“Come in, please!”

A tall man in a well-cut suit enters the workshop. Quite young for a director.

“Are you Oskar Scheubeck? Director Jansen from Oberpfalzwerke. Mr. Landauer, my engineer, recommended you to me.”

“Yes, he came to see me yesterday. Do come over, Mr. Jansen. How can I help you? It would be an honor.”

Good grief, he had forgotten the “Doctor”! Richard would be furious.

Jansen pulls some papers out of his bag and spreads them out on the workbench. Scheubeck looks at the set of complex construction drawings.

“It’s this one here,” says Jansen, pointing to a gear. “Very simple as a concept. Can you make this for me, with exactly these proportions? I need it as soon as possible. The most important thing is that you precisely follow the instructions. I repeat: precisely!”

“What is the part for?”

“I’m using it to build a tap-changer for transformers.”

“Never heard of it.”

“It doesn’t matter. The main thing is that you build this gear for me. Can I count on you?”

“Of course, Doctor!”

“Good. Let me know when you’ve done it. Good day to you, Mr. Scheubeck.”

“Goodbye, Doctor Jansen!”

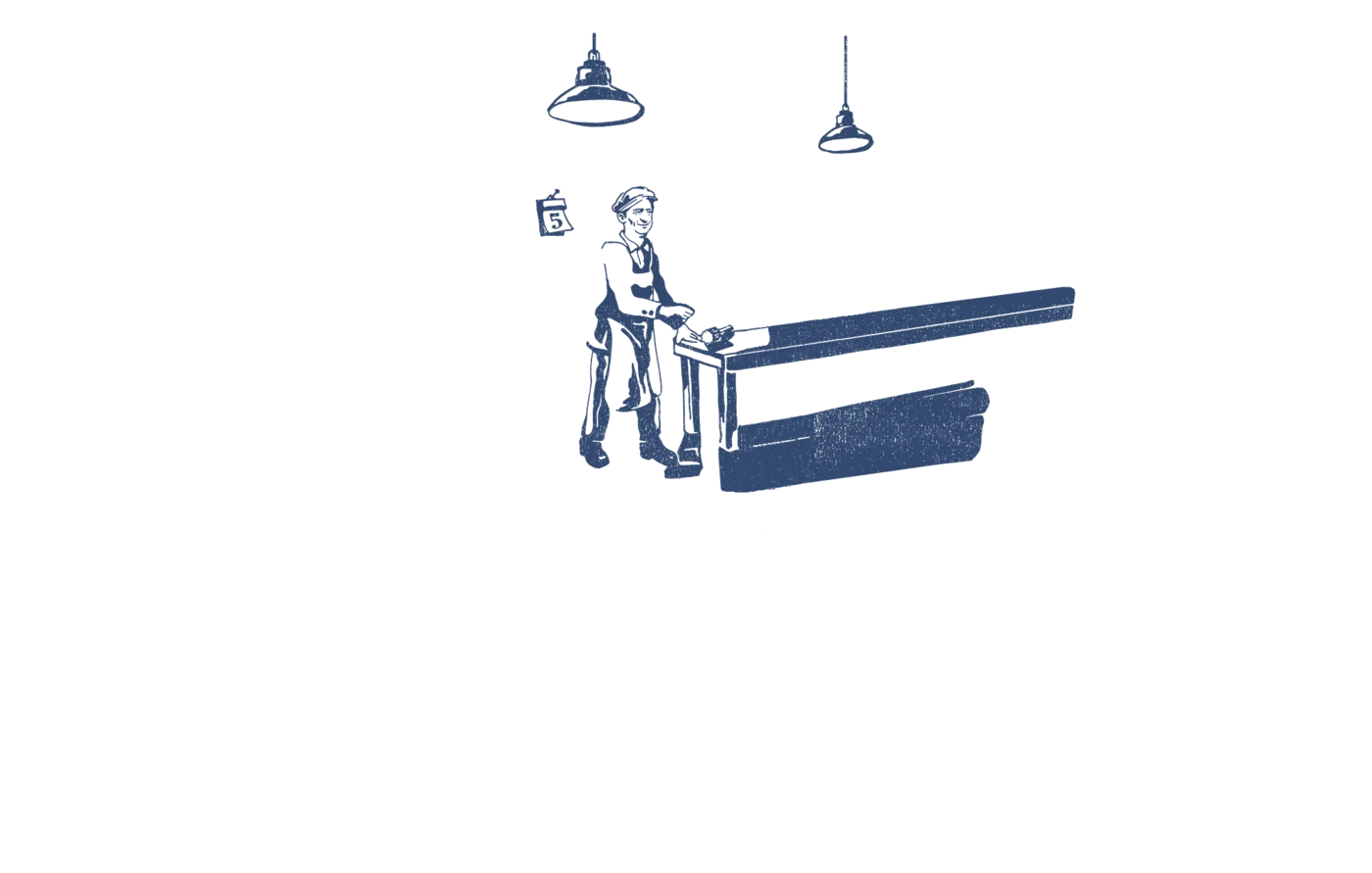

Off he went. An odd fellow. Scheubeck took his time looking at the drawing.

This awful headache!

Franz Xaver Bauer whistles a tune from “The Gypsy Baron”. Ever since the young apprentice attended the the Strauss operetta at the city hall over the weekend, it has been stuck in his head. The song and Ottilie. What an evening! After the music, they had taken a long nighttime walk to Ottilie’s house. Despite the cold, he had felt warm inside.

Finally something beautiful again! Here at the workshop, people hardly ever smiled anymore. Since the Scheubecks’ airplane crashed, the master craftsmen have been walking around with long faces. Bauer is afraid that the company is on its last legs. One colleague after another is leaving. Some stay nearby, while others go as far as Munich. People say there is still plenty of work for hardworking metalworkers there. Should he follow them? But what about Ottilie?

Xaver lais out his tools and begins filing. It would be terrible if the machine factory were to close down! His mother was so happy that Xaver had found such a good apprenticeship here.

“Xaver, come here a moment.” The young Mr. Scheubeck calls him over.

“Yes, Mr. Scheubeck.” He approaches Oskar Scheubeck’s workbench, noticing that he is staring at a couple of sheets of paper. His boss looks even more grim than he had over the last few days.

“Look, Xaver, we have a new order. The director from the power plant wants us to make this gear and he’s in a hurry to make it happen. Think about how you’d make something like this.”

“Of course, Mr. Scheubeck. Shall I work on it alone?”

“Yes please, my headacheis killing me. I’m going upstairs to lie down for a while. Richard will be back from the bank soon. You can ask him if you’re struggling with it.”

“Understood, sir.”

“One more thing, Xaver. Do your best. You never know, the director might give us more work after that. You know how badly we need this. Tell me later what you’ve come up with, alright?”

“Absolutely.”

Young Scheubeck claps him on the shoulder and heads for the stairs. Xaver Bauer looks at the drawing. It is certainly complicated. He can barely decipher the handwritten dimensions. He stays looking at it for 20 minutes. Then he decides to just get started.

Bernhard Jansen knocks on the workshop door. He had heard from Landauer that the Scheubecks had already finished the gear. Could that really be true?

“Please come in!” Jansen steps inside.

“Good evening, gentlemen.”

Jansen looks at Oskar Scheubeck standing at the workbench, with a young lad beside him wearing a hat. There is a gear on the bench. His gear. Jansen goes straight up to him and picks it up.

“Astounding! That looks very good!”

Jansen weighs the part in his hands and checks it from every side. He takes a yard stick and caliper from his bag and measures all the important dimensions. They are perfect.

“And you managed this in just a single day, Mr. Scheubeck? Unbelievable.”

“Yes, Doctor. I mean, no. It wasn’t me who did it – it was my young apprentice here, Xaver. Actually, I just wanted him to think about it, but then he went ahead and built it right away and just showed it to me.”

“Excuse me? It took you just a day to make something that six locksmiths in Regensburg couldn’t manage in weeks? How did you do it?”

The young man blushes.

“I can’t really say, Doctor. I just started and then… I can’t explain it.”

Jansen has to laugh.

“You're such a hell of a guy, Xaver!”!”

Scheubeck looks at his apprentice with a grin. The master’s pride inhis talented student. And with good reason. It was a truly extraordinary achievement.

Jansen extends his hand toward Xaver, who grasps it and blushes again.

“Well done, young man!”

Then Jansen also shakes Scheubeck’s hand.

“Do you know what, Mr. Scheubeck? If your apprentices are already smarter than the masters elsewhere, I think I’ve found my locksmith shop. I would like you to build more parts for me. Do you agree?”

“We would be truly delighted, Doctor.”

“I have some more drawings here,” Jansen says, pulling a few other pages out of his bag and placing them on the workbench. Scheubeck stands to his left, the apprentice to his right.

Jansen begins to explain.

“Right, so this is the tap-changer.”